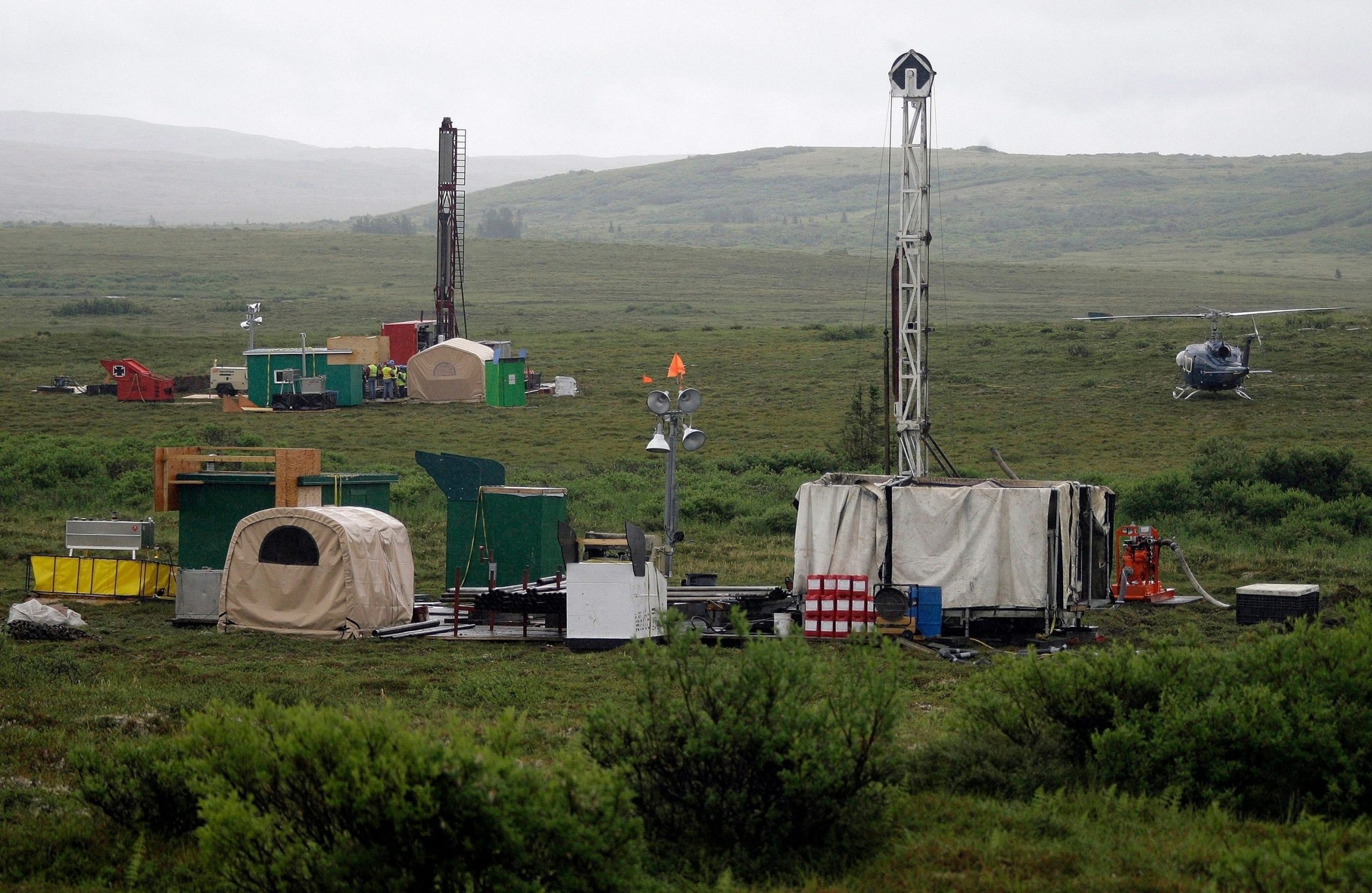

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — A proposed gold and copper mine at the headwaters of the world’s largest sockeye salmon fishery in Alaska would cause “unavoidable adverse impacts,” the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said in a letter to the developer released Monday.

The corps is giving Pebble Limited Partnership 90 days to come up with a mitigation plan for thousands of acres and nearly 200 miles of streams to secure a key federal permit to proceed. Once filed, the corps said it will decide if the plan for Pebble Mine is sufficient, David Hobbie, the corps’ regional regulatory division chief said in a letter to James Fueg, vice-president for permitting at the partnership.

It’s a seemingly stunning reversal for the corps, which just last month said in an environmental review that the proposed mine under normal operations “would not be expected to have a measurable effect on fish numbers and result in long-term changes to the health of the commercial fisheries in Bristol Bay.”

Since then, some high profile Republicans, including the president’s eldest son, have urged President Donald Trump to intervene to block the mine.

“As a sportsman who has spent plenty of time in the area I agree 100%. The headwaters of Bristol Bay and the surrounding fishery are too unique and fragile to take any chances with,” Donald Trump Jr. has tweeted.

The company said the letter is a normal part of the process, and it is working on a mitigation plan.

“A clear reading of the letter shows it is entirely unrelated to recent tweets about Pebble and one-sided news shows,” Pebble CEO Tom Collier said in a statement. “The White House had nothing to do with the letter nor is it the show-stopper described by several in the news media over the weekend.”

Collier said nothing in the letter came as a surprise, and the company was informed six weeks ago about how the corps was leaning toward mitigation plans.

“We began at that time focusing on a preliminary plan. We built two temporary camps in the watershed housing a total of about 25 people,” Collier said. “A number of teams from those camps have been mapping the wetlands in the region for about four weeks now.”

Under a section of the Clean Water Act, the corps found “factual determinations that discharges at the mine site would cause unavoidable adverse impacts to aquatic resources and, preliminarily, that those adverse impacts would result in significant degradation to those aquatic resources,” the letter to Fueg says.

Accordingly, the corps is asking for compensatory mitigation of 2,825 acres of wetlands, 132.5 acres of open waters and 129.5 miles of streams within the Koktuli River watershed for direct and indirect impacts.

The cops also determined mitigation is required for unavoidable impacts to aquatic resources from discharges along with the transportation corridor and the port site. That amount to 460 acres of wetlands, 231 acres of open water and 55 miles of streams.

“The corps lays it out. Thousands of acres of wetlands would be destroyed, 191 miles of streams would be harmed by this project, and the company has done nothing to mitigate that actual harm,” said Joel Reynolds, western director of the Natural Resources Defence Council.

The company’s current mitigation plan includes making sewage treatment upgrades, adding culverts and picking up debris along the beach, he said.

“None of that has anything to do with the devastation that this project would cause to the wetlands, to the water and to the world’s greatest wild salmon fishery,” Reynolds said.

Messages to the corps were not immediately returned over the weekend or on Monday.

Critics don’t see this as an absolute death knell for the mine, though Reynolds described it as a “nail in the coffin.”

“We are waiting for and advocating for a denial of the permit. That’s what’s going to matter at the end of the day,” said Jim Murphy, legal advocacy director at the National Wildlife Federation.

“They’ve asked for additional mitigation which I think will be very difficult, I would say impossible for the mine to come up with,” Murphy said “But I also feel that there was no way, even without these requirements, that the mine could operate in compliance with the Clean Water Act.”

If it does get the permit from the corps, the project would still face a state permitting process, along with political, economic and, likely, legal challenges. The Pebble partnership is owned by Canada-based Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., which has been looking for a partner for the venture for years.

The mine, long a source of controversy and litigation, was seen by many as getting a second wind under the Trump administration.

Under President Obama, the U.S. Environmental Protection had proposed restricting development in southwest Alaska’s Bristol Bay region. But the agency never finalized the restrictions and, under the Trump administration, allowed the Pebble partnership to go through permitting.

Mark Thiessen, The Associated Press